Table of Contents

Aral Sea Lake: A Time For Prayer

After an exhausting train journey across Uzbekistan—stretching from the capital, Tashkent, all the way to the mesmerizing desert town of Khiva, near the Turkmenistan border—we were about to embark on the most intense and fascinating adventure of our trip: a small expedition into Karakalpakstan, the autonomous Uzbek region that cradles the ghost of a great body of water, once known as the Aral Sea lake. Or rather, what little remains of it. Worn out but still buzzing with excitement (and a touch of unease), we climbed into a car at the crack of dawn on a chilly November morning in 2024. Our mission: to reach Nukus, the capital of Karakalpakstan, where our journey to the vanishing sea would truly begin. Our driver, a stocky Uzbek man with a quiet demeanor, was waiting for us outside our guesthouse in Khiva at 5 AM. Under the cover of darkness, we set off on a three-hour drive through an eerie, barren landscape—a desert littered with Soviet era remains, from crumbling factories to rusting infrastructure, relics of a lost industrial dream. The emptiness stretched endlessly in every direction, and the silence in the car, deepened by the fact that our driver spoke only Russian, made the whole experience feel surreal, like we were slipping into another dimension. Then, just as the first golden streaks of sunlight began to break the horizon, our driver suddenly swerved to the side of the road. We tensed—what was happening? Without a word, he stepped out, unrolled his prayer mat, and knelt down, his silhouette bathed in the soft glow of dawn. A devoted Muslim, he marked the beginning of our journey with a solemn prayer, as if seeking divine guidance for our passage through this forsaken land.

Aral Sea Lake: The End, unlike the Beginning, Is Known

After a brief stop at the ruins of a Zoroastrian temple—a relic of the ancient Persian faith—we rolled into Nukus, the capital of Uzbekistan’s autonomous republic: Karakalpakstan. Now, if you’ve never heard of Karakalpakstan, don’t worry—you’re not alone. But make no mistake: the Karakalpaks are a nation unto themselves, with their own language, history, and traditions. Nukus, despite its remote location (seriously, it’s practically off the edge of the map), left me pleasantly surprised. A beautiful, clean city, with stylish people striding confidently through its streets. Billboards, cultural events, and lively cafés hinted at a place bursting with an unexpected thirst for art, literature, and music. No, the Karakalpaks are far from forgotten desert wanderers—they’re cultured, curious, and very much connected to the world. Looking at Google Maps, you’d be forgiven for thinking this entire region is just one big, empty wasteland. A vast nothingness. A desert. But in reality? This land has been walked, shaped, and ruled by countless civilizations since the dawn of time. Prehistoric tribes once called it home. The Persian Empire laid claim to it. Alexander the Great marched his armies through here. It became a crucial stop on the legendary Silk Road and, later, part of the mighty Soviet Union. Karakalpakstan has always been alive—a crossroads of ideas, culture, and history. Even today, its spirit refuses to fade, standing strong like the desert itself: vast, mysterious, and full of stories waiting to be told.

Here in Nukus, our journey to the Aral Sea Lake took an exciting turn. A Mongol-featured gentleman, driving a rugged off-road vehicle, arrived to pick us up. Communication? Well, let’s just say it was an adventure of its own. Despite being a born polyglot, fluent in Karakalpak, Uzbek, and Russian, our linguistic overlap was… minimal. So, we resorted to the universal language of gestures, confused looks, and my embarrassingly basic Russian skills. As long as we had phone signal (and the sacred power of Google Translate), we managed. But soon, we lost both. Our first stop was the Mizdakhkan Necropolis, a place as mysterious as its name. Our guide, whose name I couldn’t even attempt to pronounce, began to unravel its rich history. What looks to us today like a barren, lifeless desert was once the heart of an ancient kingdom. This was Khwarazm—or, as it appears in Persian literature, Kat. A land so ancient that even the Persians themselves had lost track of its origins. Centuries later, the Muslim rulers who inherited this territory saw ruins far older than the Persian ones. This led to an astonishing belief: somewhere in this very land lay the tomb of Adam himself. Of course, where history fades, legends thrive. To this day, some Muslims believe that Adam’s grave lies among the thousands of stones scattered across Mizdakhkan. Others dismiss this idea, but insist that his real tomb must be nearby—because where else would it be? One thing is certain: a tradition has emerged. When visiting Adam’s supposed grave, pilgrims must place one stone on top of another. Why? Because legend says that when the grave is completely destroyed, it will signal the end of the world. So, in a way, these travelers—stone by stone—are buying humanity a little more time. A few extra weeks. Maybe a few extra months. A small, quiet pilgrimage to keep the universe running just a little longer. One thing kept nagging at me. How could a place once so important, so full of life, end up like this—crumbling, deserted, almost erased from time? I asked our guide, hoping for a historical explanation. Instead, in true native Slavic-speaker fashion, he launched into a passionate monologue about corruption, neglect, politicians, and oligarchs. For decades, he said, they had bled this land dry. The people suffered, poverty grew, and nothing changed. The same old story. And sure, poverty is poverty—a tale familiar across the post-Soviet world. But that still didn’t explain the dystopian wasteland stretching endlessly around us. Was it always like this?

Aral Sea Before and After

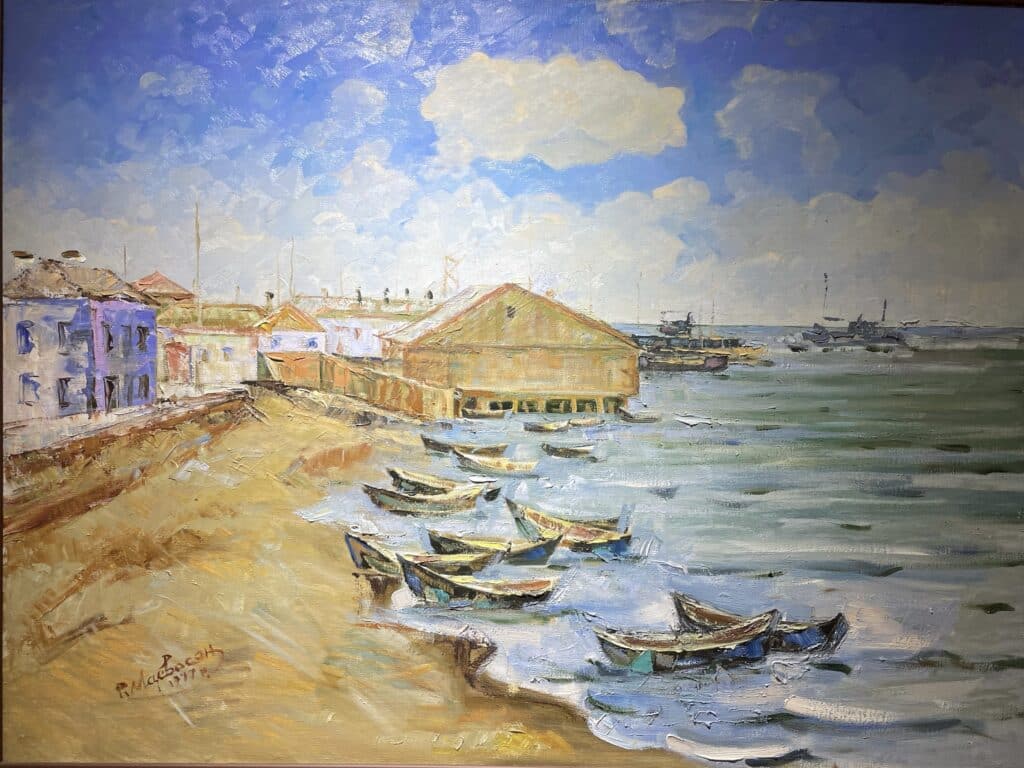

We drove on, the road stretching endlessly ahead, swallowed by a landscape of dust and silence. And then, we arrived in Moynaq. Once upon a time, Moynaq was alive—a thriving port city, bustling with fishermen, traders, and families who built their lives around the Aral Sea lake. The air smelled of salt and fresh fish, boats lined the shores, and factories hummed with industry. Caviar from Moynaq? A delicacy known far beyond these lands. But today? The sea is gone, and Moynaq stands as a ghost of itself. Instead of waves lapping at the shore, there’s cracked earth and rusting shipwrecks, stranded like giant bones of a long-dead beast. What happened here wasn’t war. It wasn’t an earthquake, a plague, or an invasion. It was something worse—something slow, invisible, and entirely man-made. The Aral Sea, once the fourth-largest lake in the world, simply… vanished. It started in the 1960s, when Soviet planners—armed with ambition but not much foresight—decided to divert the rivers feeding the sea. The goal? Cotton fields, irrigation, economic glory. The result? One of the worst environmental disasters in human history. Year by year, the water receded. Towns that once sat on the coast found themselves miles away from the nearest shore. The fish died, the industry collapsed, and the wind began to whip up toxic dust storms, laced with salt and pesticides, poisoning the land and the people who remained. Today, Moynaq is both a tragedy and a warning. A place where ships lie in the desert, where the air carries not the scent of the sea, but the ghost of what once was. And as we stood there, staring at the empty horizon where water should have been, I couldn’t help but wonder: How do you grieve a sea?

It didn’t take long for me to feel the Aral Sea’s absence in my own body. After just a few hours in the region, my throat started to burn—a dry, scratchy soreness that no amount of water could fix. At first, I thought it was just the desert air, but then I remembered: this wasn’t just dust. This was the ghost of a vanished sea, lifted by the wind and carried into my lungs. Salt, pesticides, industrial waste—decades of toxins, now part of the very air. The tragedy of the Aral Sea lake didn’t just leave behind an empty desert—it left behind sick people, poisoned lands, and a silent killer lurking in the air. With the sea gone, the wind took over, sweeping across the dry seabed, lifting salt, sand, and toxic chemicals into the sky. These weren’t just ordinary dust storms; they were storms laced with fertilizers, pesticides, and industrial waste that had settled on the seabed over decades. And where did all of that go? Into the lungs of the people. Moynaq and the surrounding areas became hotspots for disease. Rates of respiratory illnesses—chronic bronchitis, asthma, tuberculosis—skyrocketed. Babies were born with weakened immune systems, and children grew up coughing. Kidney disease, liver problems, cancer—all became disturbingly common. The lack of fresh water only made things worse. With rivers running dry and groundwater contaminated with salt and chemicals, people were left drinking polluted water. Typhoid, hepatitis, and digestive disorders became everyday struggles. And then there were the birth defects. With so many toxins in the environment, doctors started noticing an alarming rise in congenital disabilities and miscarriages. Women in Karakalpakstan have some of the highest infant mortality rates in the region. Some blame fate, others blame politics—but the truth is clear: When the Aral Sea died, it didn’t just take the fish with it. It took the health of generations and there are numerous studies to prove that. Now, Moynaq stands not just as a graveyard of ships, but as a place where the very air and water have turned against its people. The sea disappeared, but its ghosts linger—not in the waves, but in the bodies of those who still call this land home.

Aral Sea Lake: A Journey Through the Forgotten Desert

We drove for hours through a vast salt desert, swallowed by a landscape that felt utterly alien. No roads, no villages, no sign of life—just an endless expanse of white and dust, stretching as far as the eye could see. No phone signal, no internet, nothing. If something happened out here, there would be no calling for help, no passing stranger to offer assistance. It was just us, the jeep, and the howling wind. The realization settled in slowly, creeping in with the silence. We were driving across what used to be the bottom of the Aral Sea lake, a place that once lay beneath deep blue waters, now turned into a bone-dry, forgotten world. The cracked earth beneath us had not seen the sea for decades, yet it still bore the scars of long-lost currents, dried-up riverbeds, and the skeletons of an ecosystem that had simply vanished. Our guide, seemingly unfazed by the emptiness, had packed the back of the jeep with thick blankets—”just in case,” he had said with a half-smile. At first, we laughed, but then the thought settled in: what if the car broke down here? The vast nothingness around us suddenly felt heavier. The blankets, once a quirky detail, now seemed like a lifeline. It was both a comforting and an unsettling sight—a reminder that in this place, nature was merciless, and survival depended on preparedness, not luck. Along the way, we passed through stunning submarine valleys, their jagged walls once carved by currents but now left exposed to the sky—desert valleys that had never been meant to see the sun. Ancient caravanserai ruins, remnants of the Silk Road, stood stubbornly against the winds, their stones whispering tales of traders and travelers who once rested here, never imagining that one day, their stopover would sit in the middle of a lifeless salt plain.

That night, we found shelter in a yurt camp, a small cluster of round, felt-covered tents set up in the middle of nowhere, as though placed there by the hand of time itself. The air was thick with a sense of history—a strange echo of Genghis Khan’s era, when nomads wandered these endless plains and nights in a yurt were the only refuge. But now, there were no people, no laughter, no movement. We were completely alone, approximately 300 kilometers away from the nearest road—a place so isolated that the very concept of time seemed to blur. The Soviet-era metal stove inside our yurt was the only thing that gave us a sliver of comfort, but even it demanded constant attention. The cold was relentless, creeping under every layer of clothing, seeping into our bones, and making the night feel endless. Our guide, with a knowing grin, had warned us that -5°C here feels like -20°C in Moscow. He was absolutely right. The wind, like some ancient spirit, howled outside, cutting through the thin walls of the yurt. The silence was almost unnerving, broken only by the occasional crackle of the stove. Every two hours, we were jolted awake by the biting cold, forced to feed the stove with wood, our only defense against the frost. And with each refill, we found ourselves more grateful for its glowing embers, as if the warmth was a small blessing, a connection to the world beyond this frozen wilderness. In that moment, time seemed to stand still. With no one around, no signs of life, and nothing but the vast, empty landscape outside, it felt as though we had stepped into a different age, one where the world hadn’t changed in centuries. The silence was suffocating, and yet it was also a reminder of the resilience of those who once called this land home.

When the harsh winds cracks your broken lips,

And your soul is nothing but a wreck on land,

Remember, it’s not the sinking ships that hurts the most,

But the day you have no sea to command

Aral Sea Lake: Sunrise at the shore

And then, finally—morning. We arrived at what remained of the Aral Sea, just in time to see the sunrise over its still, shrinking waters. The air was crisp, the silence absolute. Along the shore, enormous salt crystals glittered in the golden light, growing larger as the water continued its slow retreat, leaving behind a sea that was more memory than reality.

On our way back, after driving for a couple of hundred kilometers away from the shore, we passed through ghost villages, their empty, crumbling buildings standing as silent witnesses to a lost era. The atmosphere was suffocating, thick with the weight of abandonment, like the land itself had been forgotten. Windows were shattered, doors hung ajar, and dust-covered streets echoed only the whispers of a time when these places were alive. Now, they were nothing more than forgotten ruins in a desolate landscape. The saddest part? There are still a few hundred people living between those ruins. We took a brief stop at an abandoned airport, its rusting tarmac and derelict control towers frozen in time, a stark reminder of the area’s once vital connections to the outside world. The eerie quiet of the place was punctuated only by the occasional howl of the wind. It felt like a world out of sync with the present, stuck between the past and an uncertain future. As we continued on, the landscape shifted into a nightmarish industrial scene. We came upon oil wells, their towering structures groaning and creaking, hungry for resources, leaking a steady stream of black gold into the air. The oil-rich land, still pumping life out of the earth, felt like a dark parody of progress. Old Soviet trucks raced wildly between the wells and nearby petrochemical factories, spewing black smoke as they made their erratic journeys, their tires screeching on the cracked, forgotten roads. The whole scene felt chaotic and desperate—a strange, disjointed dance between decay and industry, a disturbing reminder of the unsustainable force that had shaped this land.

Conclusion

As we neared the capital of Karakalpakstan, Nukus, I couldn’t help but think of the legend of Adam’s tomb. The story said that when all the stones from Adam’s grave would fall, the end would come. To me, the Aral Sea itself feels like a living embodiment of disaster and the end of times . As we neared the capital of Karakalpakstan, Nukus, I couldn’t help but think of the legend of Adam’s tomb. The story said that when all the stones from Adam’s grave would fall, the end would come. To me, the Aral Sea itself feels like a living embodiment of disaster and the end of times.

If you enjoyed reading about our expedition to Aral Sea lake, don’t forget to leave a comment below with your thoughts or questions! Also, be sure to check out more of our travel stories by visiting the rest of our blog and more photos from this adventure by following my Instagram page. And if you’re planning your own trip to the Amazon please feel free to contact me and start your own journey as soon as you can!

Leave a Reply